Keywords: traumatic brain injury (TBI), management, ICU admission

Epidemiology of TBI

Why is treatment of traumatic brain injuries (TBI) across Europe important? Traumatic brain injury (TBI) represents a medical, healthcare, social and economic burden worldwide. Approximately 82,000 deaths from all over Europe are caused by head injuries every year. It is considered that 1.4 million people in the United States are seen each year in a hospital for a TBI. From this number, 50,000 people die, 235,000 need hospitalization and treatment, and the rest are treated in the Emergency Department and released [1]. The number of people that do not seek medical help after a TBI remains unknown. This pathology represents a significant cause of death and disability all over the world, and approximately 13 million people live with disabilities related to TBI in Europe and USA. It is estimated that 10-15% of head injury patients need specialist care. Find more information on the importance of biomarkers in acute TBI and the correlation between TBI and sexual functioning.

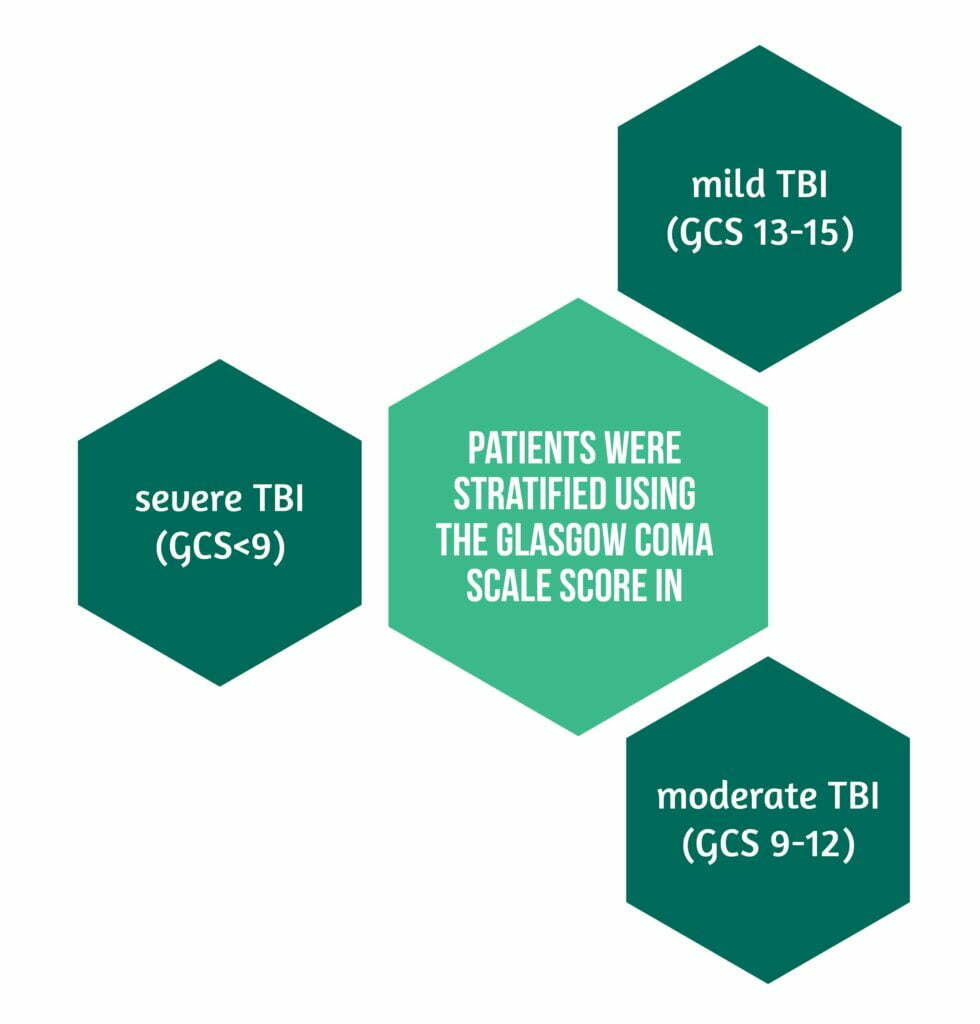

The severity of TBI in most countries is estimated using Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS). It is considered that the higher the GCS score at the initial evaluation, the better the outcome will be, and the lower the initial GCS score, the more likely the patient will remain with long-term symptoms, and this will need more extended rehabilitation.

It is considered that mild brain injuries represent 80% of all injuries, and 10% are moderate TBIs [1]. In high-income countries, the majority of patients suffering from TBIs are older than 65 years, a number that has risen by more than 50% from 2001 to 2010 [2]. Severe TBIs are usually managed in the intensive care unit (ICU) with a combined medical and surgical approach. For less severe head injuries, clinicians must decide if the patients will benefit from an ICU admission since guidelines with high-level evidence for these injuries are lacking. Previous studies showed that ICU admission was reserved for patients with severe TBIs because of the high cost of treatment in these units and the risk of overtreatment and ICU-related complications (e.g., infections from multi-resistant bacteria). Studies show that most often, ICU admitted TBI patients are young male victims involved in traffic accidents, but in recent years ICU admission policies have changed, and patients with milder TBIs are being treated and monitored in the ICU[2,3].

The story of CENTER-TBI

The Collaborative European NeuroTrauma Effectiveness Research in Traumatic Brain Injury (CENTER-TBI) was a longitudinal prospective study aimed to provide a general description of ICU admission policies, management, and outcome for traumatic brain injury (TBI) patients from Israel and Europe. Inclusion criteria were:

- clinical diagnosis of TBI

- indication for a brain CT scan

- presentation to the hospital within 24 h after the injury

The exclusion criterion was a pre-existing severe neurological disorder that may influence the outcome assessment. The medical ethics committees of all the participant centers approved the study. Informed consent was obtained from every patient or legal representative.

The study analyzed patients directly admitted from the Emergency Department and patients transferred within 24h from the injury from another hospital to their ICUs. Patients who deteriorated in the trauma, neurological, or neurosurgical ward or were (re)admitted to the ICU were excluded.

Clinical data were collected:

- at the ICU admission

- during ICU stay

- at ICU discharge

Patients were stratified using the Glasgow Coma Scale score in mild (GCS 13-15), moderate (GCS 9-12), and severe TBI (GCS<9).

Monitored intracranial pressure and cerebral perfusion pressure values every two h for selected patients. Intracranial hypertension was defined as a value above 20 mmHg. For cerebral perfusion pressure, the threshold was set at 60 mmHg. In addition, an updated version of the therapy intensity level scale (TIL) was used to quantify ICP-targeted therapy’s intensity, and other aggressive treatments for raised ICP were analyzed, such as hypothermia and intense hypocapnia barbiturates, and decompressive craniectomy.

The outcome was measured six months after the TBI using a variation of the Glasgow Outcome Scale-Extended (GOSE) that combined “vegetative state” (GOSE 2) and “lower severe disability” (GOSE 3), resulting in a seven category ordinal scale.

Different statistical tests were used for categorical and continuous variables to compare patient characteristics, treatments, and outcomes. The variation between centers was quantified using random-effect logistic and ordinal regression models with a random intercept for the center and expressed as the median odds ratio:

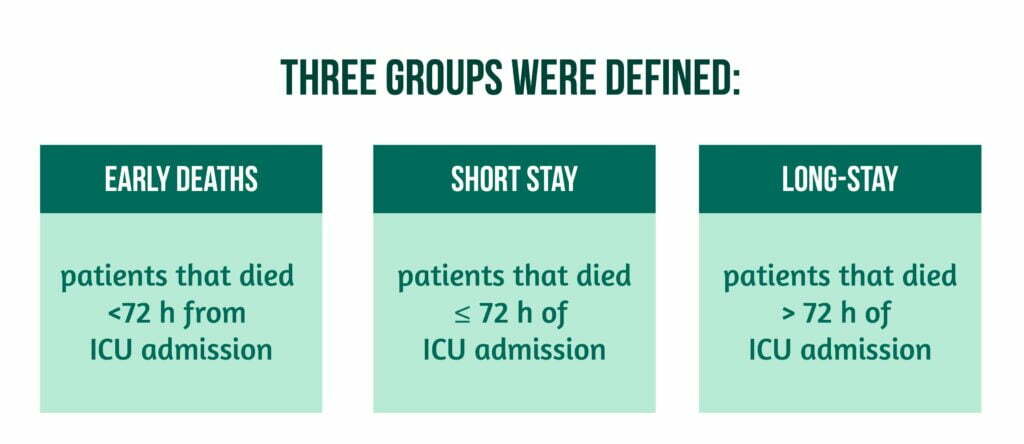

- for the proportion of patients with a short stay (≤ 72 h in the ICU) versus early deaths (<72h) and long stay (>72h in the ICU)

- for the proportion of cases that have received ICP monitoring, and also a sensitivity analysis was performed for the proportion of cases that received ICP treatment in the group of patients with an abnormal CT scan and a GCS≤8

- for the proportion of patients that needed aggressive ICP-lowering treatments (hypothermia therapy, decompressive craniectomy, intensive hypocapnia, and metabolic suppression)

- for the 6-month GOSE outcome.

CENTER-TBI Results

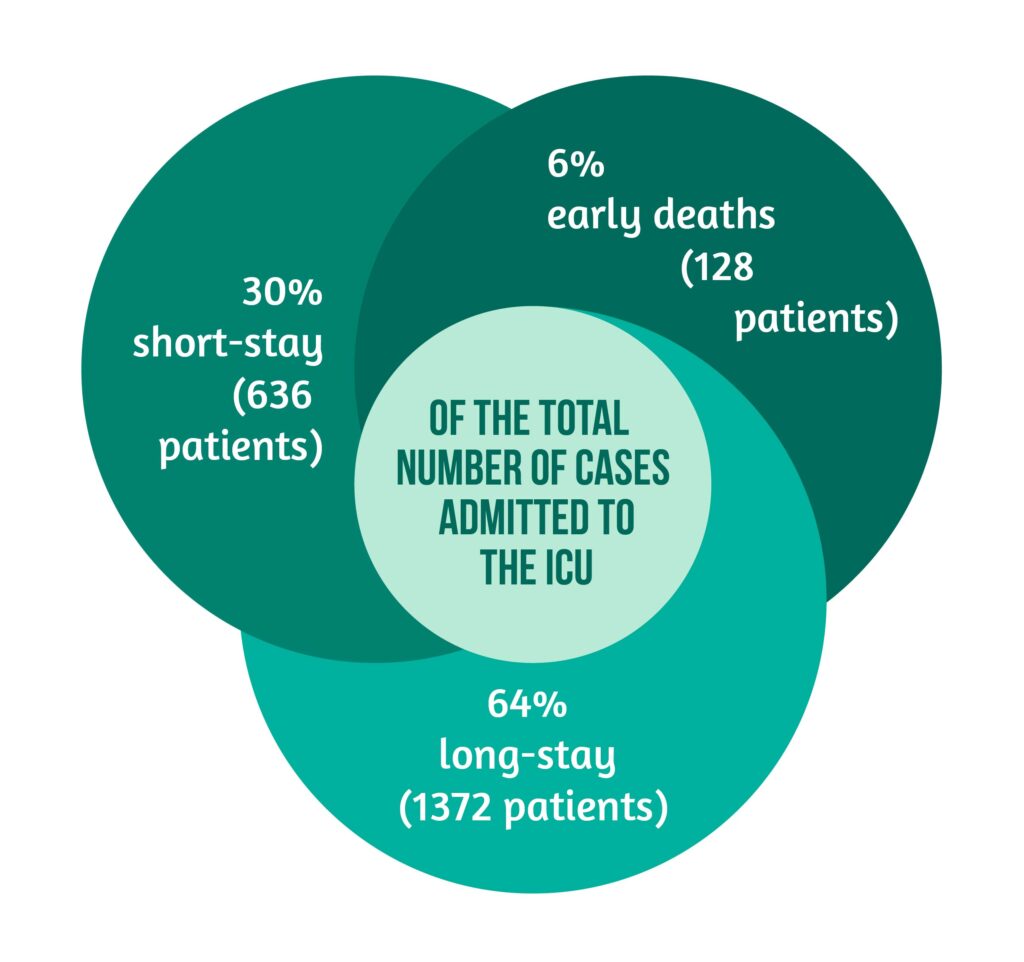

The CENTER-TBI study enrolled 4509 patients, of which 2138 were admitted to the ICU and after that were included in the study. The results showed that patients were primarily men (73%), the median age was 49 years, and the majority of TBIs admitted to the ICU were severe. Approximately 36% of the patients admitted to the ICU had mild symptoms. Only a minority of patients were children younger than 18 years, 26% were older than 65 years, and 4% were older than 80 years. Over half of the patients major extracranial injuries were present. The median length of ICU stay was 11 days. In the first 72 hours, mortality and discharge rates were high after admission to the ICU but declined over time.

Cases distribution

Higher median age and more severe extracranial and intracranial injuries had early death patients compared to survivors.

Demographic features were approximately the same between short- and long-stay groups, but significant differences were observed regarding the severity of the injury, pre-admission insults, and CT findings.

Long-stay patients and patients who died early were the main categories that needed mechanical ventilation for at least 24 h in comparison to short-stay patients. The main indication for ICP monitoring in short-stay patients was surveillance after an intracranial operation. Long-stay patients and early deaths usually needed invasive blood pressure monitoring. Also, extracranial surgery and neurosurgical interventions were more frequent in long-stay patients and less frequent in short-stay ones. Patients in the last category (short-stay) needed less aggressive ICP treatments like decompressive craniectomy, intensive hypocapnia, hypothermia, or metabolic suppression.

Complications

Complications due to head injury were the leading cause of mortality in the early death group. The most frequent reasons for short-stay patients (<72 h) ICU admissions were the need for neurological observation or mechanical ventilation. For the long-stay group of patients, which consisted of 25% from mild TBIs, the reasons for ICU admission were similar (neurological observation or mechanical ventilation).

Complications were more frequently observed in long-stay patients and most commonly were ventilator-acquired pneumonia and cardiovascular complications. The overall median hospital length of stay for short-stay patients was 11 days, while it was 18 days for long-stay patients. Short-stay patients were usually discharged to a step-down unit or transferred to the ward compared to long-stay patients. In addition, long-stay patients were often discharged to other hospitals or rehabilitation units. Rarely were these patients discharged to other locations (like homes, nursing homes, or other ICUs).

In the ICU stratum, the in-hospital mortality was 15%, and at six months, it rose to 21%. As expected, six-month mortality was higher in long-stay patients than in short-stay patients and observed an unfavorable outcome (GOSE<5) in 50% of long-stay patients compared to 15% in the short-stay group and 43% in the ICU stratum.

The data also revealed significant differences between centers in short- vs. long-stays and early deaths (<72 h). However, between-center variations in the outcome were smaller in comparison to the variation in the treatment.

Study conclusions on treatment of traumatic brain injuries

The CENTER-TBI study showed a strong contrast with historical TBI series, showing that a substantial proportion of patients admitted to the ICU were diagnosed only with mild or moderate TBI. We must keep in mind that those studies included only severe TBI patients, so we cannot evaluate the general policies for ICU admission at the time. The study revealed that 68% of the centers questioned regarding the ICU admission for patients with GCS between 13-15 and a normal CT scan reported this as consistent with their center policy.

Of the admitted cases, approximately 6% of the patients died in the first 3 days from admission with severe extra-cranial and intracranial injuries. Patients in this group were older, and approximately half of the group who had documented intracranial mass lesions received an operation. The survivor group was divided into two groups: those with a short transition through the ICU and those with a longer duration of treatment in the ICU. The 72h limit was selected as the separation criterion between these groups, keeping in mind the high discharge rate in the first 3 days. The 72h mark spotted patients that had different clinical characteristics, different care pathways, and different outcomes.

Long-stay patients had more severe injuries and frequently required invasive monitoring, including ICP and therapies (surgical or medical). They usually had worse outcomes than short-stay patients. In comparison, short-stay patients had less severe injuries, needed less monitoring and treatments, and had better outcomes. As discussed above, the main reasons for ICU for these patients were only the need for neurological observation and mechanical ventilation, which was continued for 24h only in approximately a third of cases. These were considered to be a reflection on the early intubation at the scene of the accident or during the evaluation and assessment policy. This might be considered a prudent strategy that offers close assistance and surveillance to relatively low-risk patients and offers them the opportunity for a good outcome. One must keep in mind that the risk of deterioration is low but non-negligible in mild TBI patients. Recent studies estimate a 12% incidence of neurological deterioration and a 3.5% need for neurosurgical intervention for patients with mild TBI (GCS 13-15). On the other hand, these admission strategies may represent a costly over-triage since the ICU is an expensive resource that should use wisely. The direct discharge home from the ICU of the 11 patients from the short-stay group raises strong reservations regarding their need for intensive care treatment.

Lessons from CENTER-TBI

Previous studies estimated that approximately 17% of cases in the USA were over-triaged (this was defined as shorter than 1 day ICU stay or shorter than 2 days hospital stay, no need for intubation, no need for neurosurgery, and the patient was discharged home). The data from the CENTER-TBI study is partially concordant with these other studies. Even if they do not permit accurate cost-benefit analysis, they indicate a shift in the ICU admission policies that needs more attention. The study also revealed a significant between-center variation in admission and discharge policies, especially for mild TBI patients, a variation that might be explained by a lower adherence to guidelines, a search for more individualized case management, and different resources that are available or various combinations of all these factors. Between-centers variations in outcome were smaller than previously reported in other studies, a fact that might show an evolution in TBI treatment in Europe and Israel during the last years.

Compared to previous data, the CENTER-TBI study revealed that the population admitted with TBIs has changed in the last years across Europe, with milder TBis and older patients being admitted to the ICU primarily for monitoring and treatment of traumatic brain injuries. This shows that nowadays, clinicians prefer a more prudent strategy offering close surveillance to patients at relatively low risk in order to ensure good outcomes, but also that they know that even if the risk of deterioration is low in a mild TBI, it is non-negligible.

References

1. Greenwald, B. D. & Rigg, J. L. Neurorehabilitation in traumatic brain injury: does it make a difference? Mt. Sinai J. Med 2009, 76, 182–189, DOI: 10.1002/msj.20103

2. Stocchetti, N. et al. Severe traumatic brain injury: targeted management in the intensive care unit. Lancet Neurol 2017, 16, 452–464, DOI: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30118-7

3. Majdan, M. et al. Severity and outcome of traumatic brain injuries (TBI) with different causes of injury. Brain Inj 2011,. 25, 797–805 (2011), DOI: 10.3109/02699052.2011.581642