Authors: Andres Munive 1, Luis F. Carbonell 1, Yancarlos Ramos-Villegas 1 , Tariq Janjua2, Luis Rafael Moscote-Salazar 1

- Colombian Clinical Research Group in Neurocritical Care, Bogota, Colombia

- Department of Critical Care Medicine, Regions Hospital. Saint Paul, MN, USA

Prevention of Neurotrauma is the Best Treatment

The prevention of neurotrauma is a challenge for all health systems and represents a problem for public health, being more frequent than currently prevalent diseases such as HIV/AIDS and breast cancer [1]. This is a cause of a large number of deaths in the population, both nationally and globally [2]. The craniocerebral lesion not only results from the initial physical injury but can also occur later in the course of the active treatment phase [3]. Because of this, an increase in prevention campaigns should be encouraged, where the main preventive measures should be the use of a helmet, safety belt, and safe driving [4].

If you want to learn more about neurotrauma, check out:

- Neurotrauma and Info-pollution: A call for action

- Traumatic Brain Injury Registries? Yes!

- The Surgeon’s Perspective – Lessons from NTSC

- TBI in Europe – new insigths

Epidemiology and impact of neurotrauma on society

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is defined in Figure 1 [2].

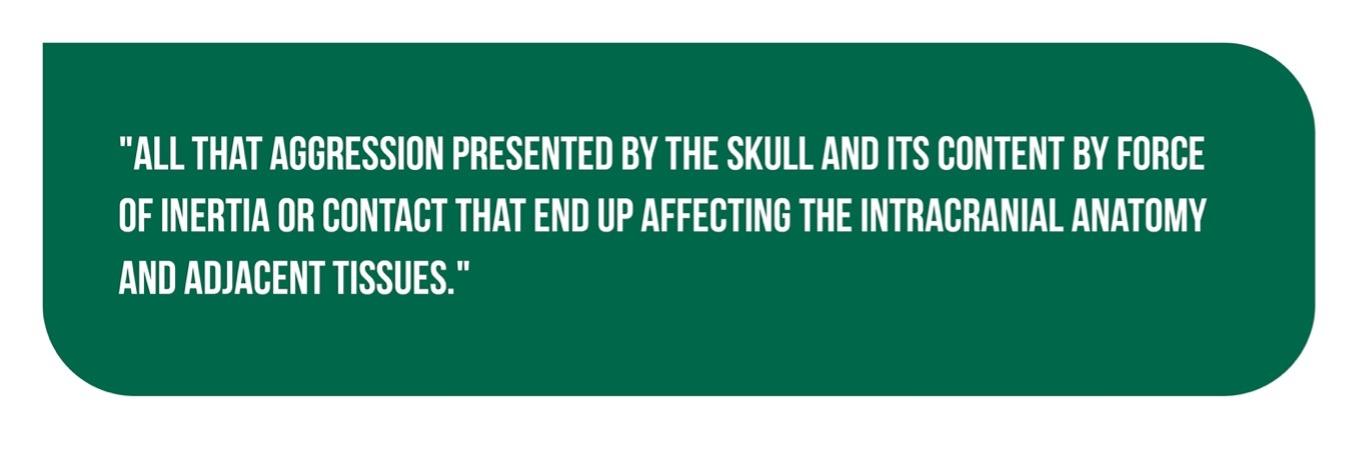

Globally, TBI brings with it a large number of disabilities and a high mortality rate [4]. It is estimated that the worldwide incidence is approximately 200 cases per 100,000 inhabitants and that the overall mortality for unselected groups of traumatized patients fluctuates between 8% and 22% [2]. In the United States, craniocerebral trauma accounts for almost a third of all deaths related to injuries (Figure 2), in addition to about 13 million emergency admissions, which represents 4.8% of visits related to injuries and 1.4% of all consultations [3].

However, the lack of epidemiological data from medium and low-income countries represents a problem in providing global and specific data regarding injuries caused by neurotrauma [2]. In Colombia, injuries occur mainly in the most active economic population of males between 12 and 45 years old [4]. In 2013, about 26,000 deaths from trauma were reported, of which a large percentage were associated with head trauma [5].

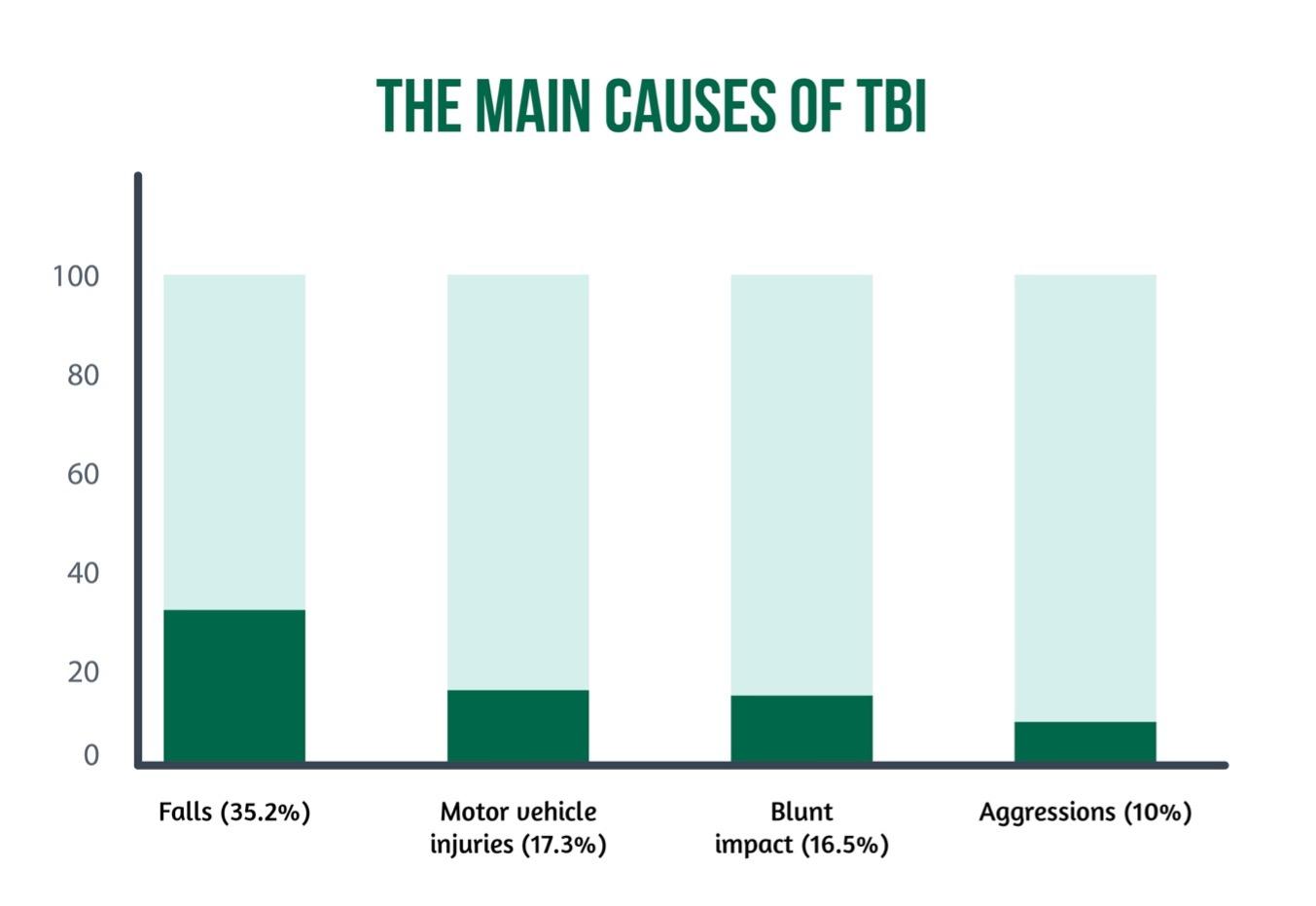

The main causes of TBI are falls (35.2%), motor vehicle injuries (17.3%), blunt impact (16.5%), and aggressions (10%), which to a large extent, can be avoided by preventive measures such as the use of a seat belt and helmet [6] (Figure 3).

Prevention in neurotrauma

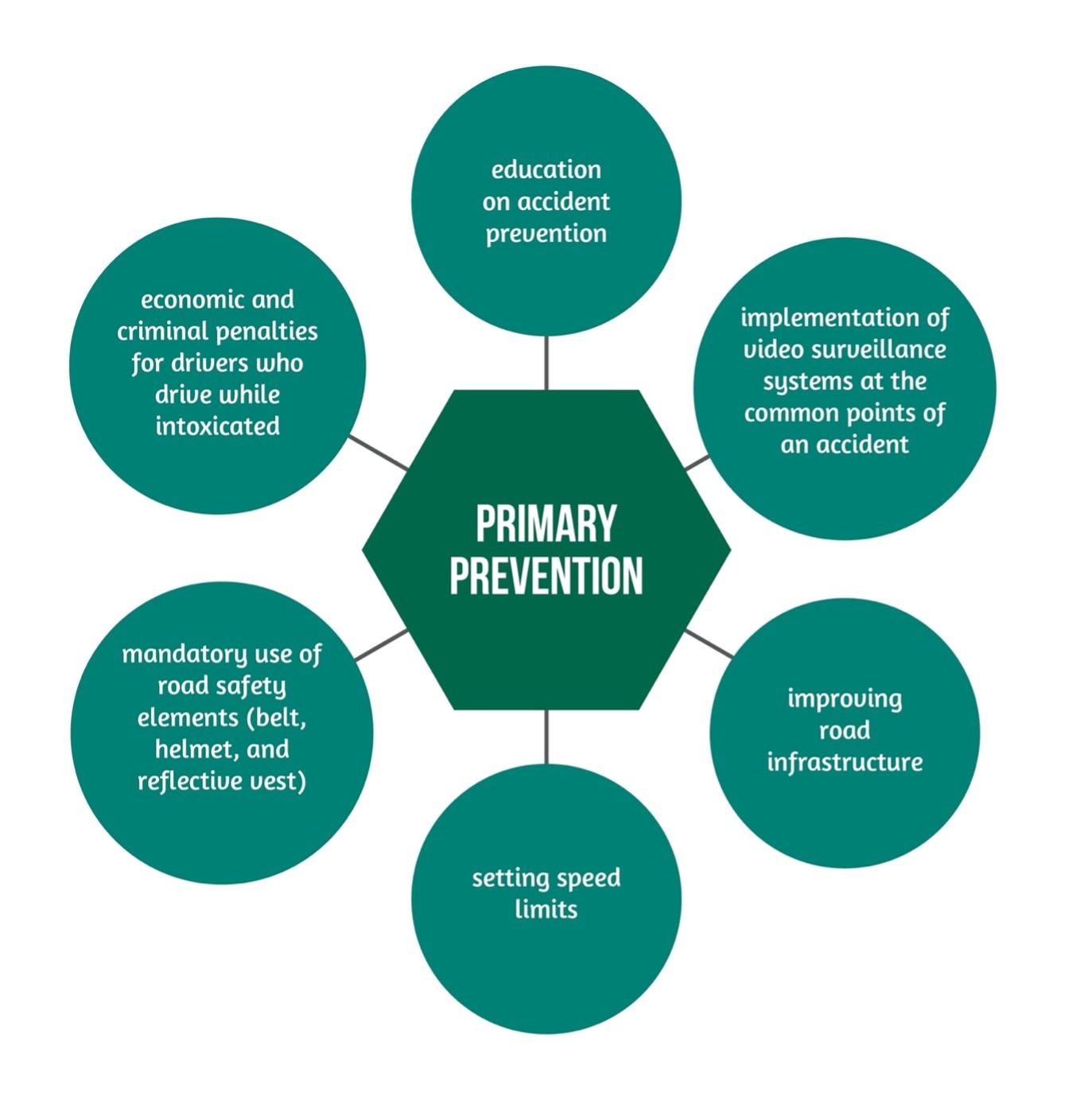

The prevention of neurotrauma includes 3 levels of intervention; the first seeks that the trauma never occurs and is known as primary prevention, and the second level of intervention is called secondary prevention, which seeks to reduce the resulting damage once the trauma has occurred [7]. In the third level (tertiary prevention), measures have been adopted that favor the rehabilitation of the sequelaes to increase the functional capacity of the individual [8]. The latter two are beyond the scope of this article.

Because traumatic injuries at the level of the nervous system entail high morbidity and mortality, great efforts are currently being made around primary prevention [9].

These actions include the following, showcased in Figure 4 [2,8].

The American Congress of Neurosurgeons and the American Association of Neurosurgery, since 1986, have been implementing the program Think First [10]. The objective of this program is to reduce the incidence and severity of spinocranial trauma. This is aimed at school-aged children, parents with young children, and the elderly. Its methodology includes audiovisual aids, testimonials, and group discussions [11].

In 1995, the previous model served as a guide for the Brazilian Society of Neurosurgery to start the Think Good program (in Portuguese Pense Bem) [2,10]. Falavigna et al., in 2014, using a randomized controlled trial with a sample of 535 students from 6 schools in Brazil, determined that even though 95% are aware of the proper use of the safety belt, the sample composed of Fifth grade elementary and second-year students who received multiple educational and awareness campaigns, did not change their behavior regarding the use of personal protective equipment when handling bicycles, skateboards and roller skates in relation to the control group [10]. Additionally, Gaiad T et al., in 2018, in a similar population in Brazil, established that of 451 students, 41% had no knowledge about spinal cord trauma, and 52% of head trauma. Additionally, 94% had already consumed an alcoholic beverage [12].

The previous data invites us to reflect on the importance of continuing and optimizing these programs and thus being able to continue contributing to the decrease in deaths related to this phenomenon [8].

Conclusions

Despite the implementation of various intervention campaigns in groups defined as priorities, such as school-age children, adolescents, parents with young children, and the elderly, humanity continues to exhibit behaviors that make them susceptible to neurotrauma. This forces institutions to optimize the current methodology to generate a greater impact, increasing a greater number of actors so that they handle the same language, knowledge, and attitude toward the identification of hazards leading to TBI.

References

- Parsons D, Colantonio A, Mohan M. The utility of administrative data for neurotrauma surveillance and prevention in Ontario, Canada. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5(1):584. DOI: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-584

- Moscote-salazar LR, Rubiano AM, Moscote-salazar LR. Prevencion en Neurotrauma : De la Promoción de la Seguridad a Las Tácticas de intervención. Arch Med. 2016;12(3:4):22–4. Available at: https://www.itmedicalteam.pl/articles/prevencion-en-neurotrauma-de-la-promocioacuten-de-la-seguridad-a-las-taacutecticas-de-intervencioacuten-103339.html

- Chang W-TW, Badjatia N. Neurotrauma. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2014;32(4):889–905. DOI: 10.1016/j.emc.2014.07.008

- Charry JD. Guía colombiana de práctica clínica para el diagnóstico y tratamiento de pacientes adultos con trauma craneoencefálico severo Recomendaciones relacionadas con la atención inicial de urgencias. Minist Protección Soc. 2016. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326381380_Guia_colombiana_de_practica_clinica_para_el_diagnostico_y_tratamiento_de_pacientes_adultos_con_trauma_craneoencefalico_severo

- Lozano Losada A. Trauma craneoencefálico aspectos epidemiológicos y fisiopatológicos. RFS Rev Fac Salud. 2009;1(1):63–76. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25054/rfs.v1i1.40

- Chang WW, Badjatia N. Neurotrauma. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2014;32(4):889–905. DOI: 10.1016/j.emc.2014.07.008

- Char SB. Traumatic brain injury: Can the consequences be stopped? Can Med Assoc or its Licens. 2008;178(1):1486–90. DOI: 10.1503/cmaj.080282

- Hoz S, Moscote-salazar LR, Moscote-salazar LR. Prevention of neurotrauma: An evolving matter. Neurosci Rural Pract. 2017;8(5):141–3. doi: 10.4103/jnrp.jnrp_194_17

- Reilly P. The impact of neurotrauma on society: an international perspective. In: Progress in Brain Research [Internet]. 2007. p. 3–9. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0079612306610017

- Unit N, Alegre P, Alegre P. How can we teach them about neurotrauma prevention? Prospective and randomized “Pense Bem—Caxias do Sul” study with multiple interventions in preteens and adolescents. Neurosurg Pediatr. 2014;94–100. https://www.academia.edu/79175436/How_can_we_teach_them_about_neurotrauma_prevention_Prospective_and_randomized_Pense_Bem_Caxias_do_Sul_study_with_multiple_interventions_in_preteens_and_adolescents

- National Injury Prevention Foundation. ThinkFirst : Primary Prevention That Makes a Difference The Premier Resource for Injury Prevention Educational Programs Since 1986. 2015. Available at: https://www.thinkfirst.org/sites/default/files/About%20ThinkFirst.pdf

- Santos AP. projeto neurotrauma: educar para prevenir-o melhor. Rev Ciência em Extensão. 2018;14(1):70–80. Available at: https://ojs.unesp.br/index.php/revista_proex/article/view/1814