Keywords: TBI, burden, CENTER-TBI, falls

Low-energy falls and TBI – insights into neurotrauma

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a significant medical, healthcare, and social issue worldwide [1]. Although the epidemiological aspects have been studied in different populations, describing and quantifying their global patterns is complicated due to the lack of geographical, time- and definition-related variability as well as standardized data collection [2].

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States estimated 2,53 million patients undergoing TBI-related emergency department (ED) visits, out of which 288.000 needed hospitalization, and 6.800 died due to the injuries. The data included both children and adults [3].

The issue of classification

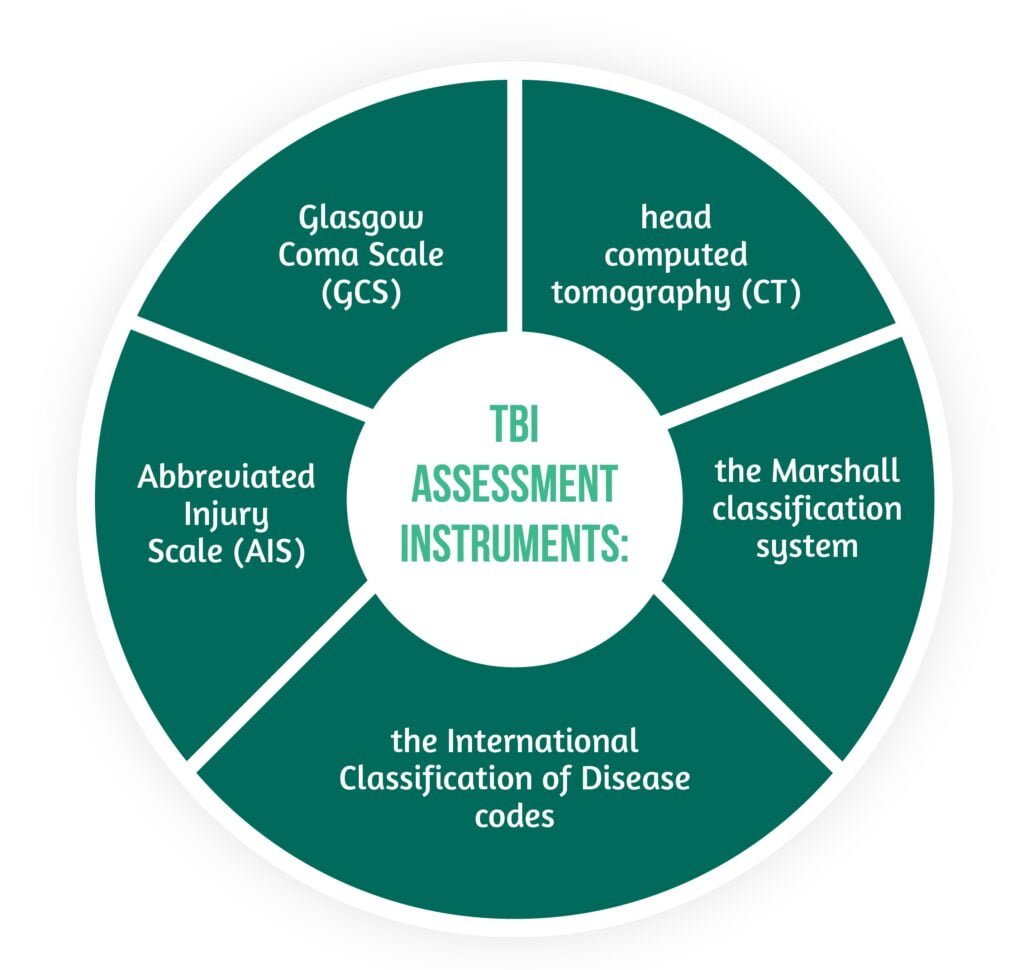

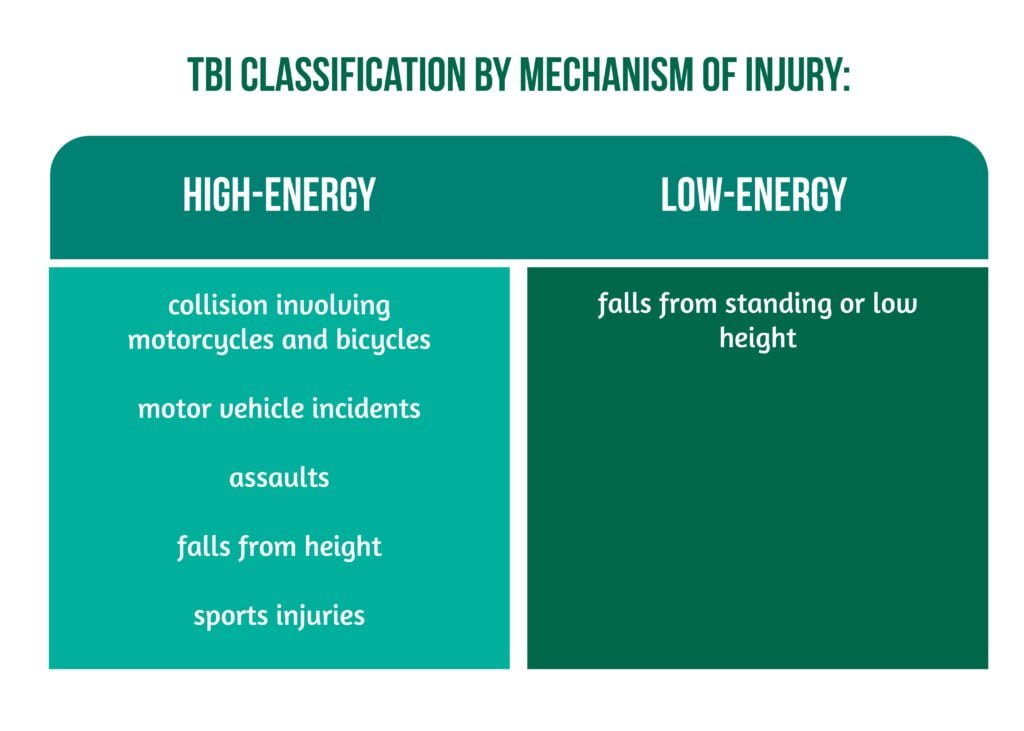

Injury classification by energy transfer mechanisms (high-energy transfer vs. low-energy transfer) has received increased attention in general trauma care and emergency medical service (EMS). This classification aids in conducting better triages. Furthermore, patients suffering from high-energy transfer injuries can be relocated to higher levels of care within specialist trauma centers. This prioritization is underpinned by the assumption that high-energy transfer injuries are more likely to result in tissue damage that can be life-threatening. However, the TBI burden is usually revealed by the scales showcased in Figure 1.

Recent studies challenge this paradigm of prioritizing high-energy transfer mechanisms as the best strategy for reducing the burden of TBI. Research shows that falls represent the leading cause of TBI in older people all over Europe and in high-income countries. Older patients suffer from multiple age-related changes in the brain and blood vessels, increased risk of consequent significant intracranial injury, and decreased recovery potential. Therefore, a specific focus on the burden of low-energy TBI disease is required, along with appropriate injury prevention, trauma center triage priorities, and EMS care [4].

The Collaborative European NeuroTrauma Effectiveness Research in Traumatic Brain Injury (CENTER-TBI) study was developed in 56 centers from 18 European countries and Israel and took place between 2014 and 2017, aiming to improve doctors’ understanding of TBI [5]. Lecky et al. present a comparative cohort study using data from CENTER-TBI for patients presenting with TBI and an indication for a CT scan [4].

The aim of the study was to determine:

- the prevalence of low-energy falls causing TBI within the whole cohort

- the comparisons between patients who suffered a TBI caused by a low-energy fall versus a high-energy transfer in terms of:

- injury characteristics

- demographics

- hospital mortality

- care pathways [4].

Methods

The CENTER-TBI study included patients of all ages with a suspected or clinical diagnosis of TBI between 1 December 2014 and 31 January 2018 that underwent a CT scan. No exclusion criteria existed for recruitment. The research also included data from patients with pre-existing cognitive impairments such as dementia, severely injured patients who died in the Emergency Department (ED) room prior to imaging, and patients presenting more than 24 h after the injury [4].

The variables collected included:

- demographics (sex, age)

- pre-existing health status (e.g., treatment with anticoagulants or antiplatelets previous to the injury)

- mechanism of injury

- injury severity descriptors (AIS and Glasgow Come Scale)

- vital physiological signs (oxygen saturation, blood pressure, pupillary response)

- CT brain findings – classified as the presence/absence of small/large epidural hematoma/acute subdural hematoma/brain contusion, midline shift, subarachnoid hemorrhage, basal cistern compression, individual patient Marshall grading of CT findings

- process of care (e.g., intubation upon arrival at the trauma center, referral method)

- time from hospital arrival to CT scan

- intensive care unit (ICU) admission

- key emergency interventions (craniotomy, decompressive craniectomy, external limb fixation, intracranial pressure monitoring, emergency laparotomy, thoracotomy, extraperitoneal pelvic packing)

- an immediate outcome of care regarding:

- length of stay

- hospital mortality

- destination on discharge (home, another hospital, nursing home, or rehabilitation center) [4].

The variables were chosen using the Utstein trauma template for standard trauma registry collection across Europe, Australia, and North America.

The TBIs were classified as shown in Figure 2.

The research was conducted in accordance with all relevant laws of the European Union and all the laws of the country where the recruitment center was located, including the ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline for Good Clinical Practice and the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained for all recruitment sites.

Results – what CENTER TBI revealed regarding low-energy falls

The total number of patients enrolled was 22 782, and the study outcomes were analyzed for 21 681 patients suffering from TBI with a known injury mechanism. Of the total number, approximately 40% of patients were injured by a low-energy fall (LE cohort).

The majority of patients needed admission to the hospital, and 19% of them were in the ICU. CT scan showed abnormalities in 31% of patients, the most common being small cerebral contusion, small subdural hematoma, and subarachnoid hemorrhage. In moderate TBI, extracranial injuries were present, and in 11% of patients, key emergency interventions were needed (the most common being craniotomy in the first 3 hours since arriving in the ED). Most of the patients (71%) were discharged from the hospital to their own homes.

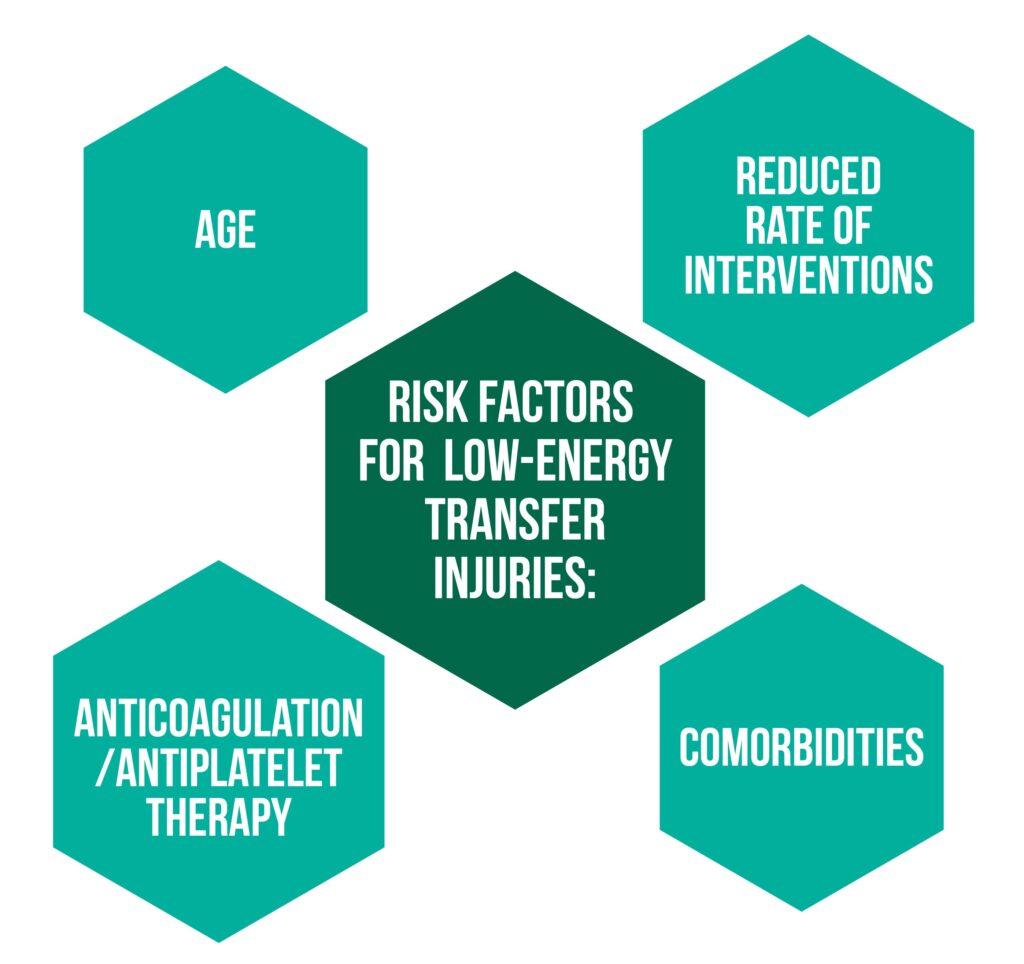

More than half of the patients suffered a high-energy TBI, mostly due to road traffic accidents, assaults, and falls from a height, while 40% of them were injured as a consequence of low-energy falls. The prevalence of low-energy transfer injuries varied from 30% to 50% in most participating centers and countries. Compared to the high-energy transfer (HE) cohort, the LE cohort patients were older, with a median age of 74 years, more often female, more frequently with the chronic treatment of anticoagulants or/and platelet aggregation inhibitors, and more likely to have suffered the injury at home.

Also, they were less often presenting with severely or moderately impaired consciousness levels, less likely to arrive to the hospital intubated or by secondary transfer, and more likely to have a delayed brain CT scan [4].

Compared to high-energy transfer TBIs, patients presenting with injuries due to low-energy falls had fewer abnormalities on the CT scans and fewer intracranial injuries on the abnormal ones. In addition, the ones that LE cohort were more likely to use anticoagulants or platelet aggregate inhibitors, or both compared to the high-energy cohort. A greater time delay was observed between the arrival of patients at the hospital and the emergency interventions in the low-energy falls TBI group, but this difference was statistically significant only for patients receiving craniotomy.

Both groups had similar in-hospital mortality; however, there was a greater period of time between the moment of arrival at the hospital and the time of death for the LE cohort. The rate of home discharge was lower and the one for nursing homes was higher in the low-energy TBI group compared to the high-energy transfer cohort, but similar rates were in both groups in the referral for rehabilitation and transfer to other hospitals.

When assessing care pathways, mortality in the low-energy falls group was higher in ICU patients and four times greater in admitted patients compared to the high-energy cohort. In patients with TBI admitted to the ICU or ward, the characteristics most often used as predictors for in-hospital mortality were older age, a high Marshall score with a non-evacuated mass lesion, pre-injury comorbidities, and the use of anticoagulation medication [4].

Discussions

CENTER-TBI was a unique large-scale project that aimed to improve TBI patients’ characterization to allow better targeting of therapies and identify best practices through comparative effectiveness research [6]. The study also reveals that 40% of patients had a low-energy TBI. Moreover, the results suggest an acute need for clinical care pathways and priorities review for the group that suffered low-energy transfer injuries. The risk factors for the demographic most prone to this type of injury are showcased in Figure 3.

The pre-existent comorbidities and the age-related intracranial changes might have also contributed to the higher GCS score at presentation for older patients compared to younger ones. These findings reflect the need for a holistic, multidisciplinary, personalized approach for TBI patients that require acute care, to address each patient’s specific interaction between pre-existing health issues and sustained brain injury.

Overall, researchers found a higher incidence of intracranial hemorrhage in patients following treatment with antiplatelet medication compared to anticoagulant therapy. These results are similar to others from the literature, possibly because the anticoagulation medication can be reversed while antiplatelet therapy cannot. This is why imaging guidelines should be updated and give as much attention to antiplatelet medication as to anticoagulation therapy.

The similar hospital admission and mortality rates between the two groups challenge the current paradigm focusing on the prioritization of high-energy TBIs. In addition, the assumption that energy transfer is proportionate to the severity of intracranial lesions is not valid in the case of older TBI patients [4].

Strengths and limitations

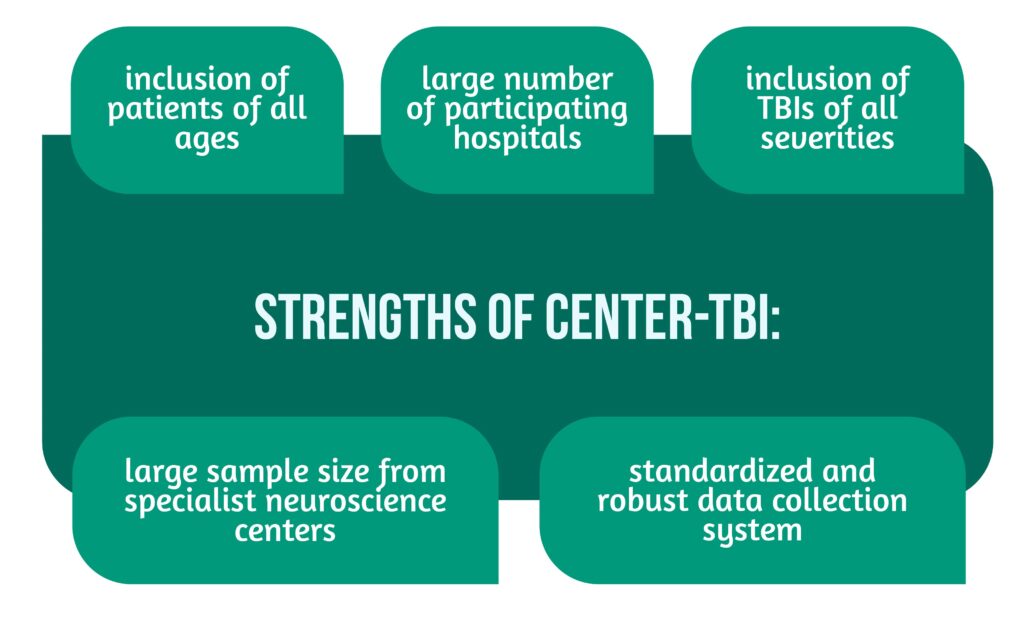

The CENTER-TBI study had general strengths, as highlighted in Figure 4.

In contrast, there are some limitations to the current study, such as the lack of availability of disability rates beyond discharge. Also, the registry did not record if there was any alcohol ingestion that might have contributed to both types of TBIs. Patients from the registry with an unknown mechanism of injury were excluded (approximately 5%). This might result in possible misclassification by the prehospital staff.

Due to the fact that most participating centers were hospitals that receive a high proportion of TBI patients directly from the EMS triage, bypassing closer hospitals that do not have the needed specialists or by secondary transfer, the proportion of patients suffering from low-energy transfer TBIs across Europe might be higher than 40% [4].

Conclusions

TBI remains one of the most important brain pathologies nowadays, and the burden of it is widely recognized as an important medical and healthcare problem worldwide.

The current study is an example of the high heterogeneity of TBI as a disease, and it might be the largest one to describe the two cohorts and highlight their differences. Doctors should recognize the life-threatening potential of low-energy falls, especially in older patients following treatment with anticoagulants or antiplatelet medication. Further studies are needed in order to justify the use of critical care and emergency interventions for those who suffer low-energy falls resulting in TBI.

The reduction of the burden TBI has worldwide can only be achieved through guidelines targeted at managing and preventing TBIs resulting from both low- and high-energy transfer mechanisms and through public health policies.

To understand more about the intricacies of Neurotrauma, visit:

- The importance of prehospital care for severe TBI

- Predicting access to rehabilitation: the CENTER-TBI approach

- Osmotherapy in severe TBI

Bibliography

- Majdan M, Plancikova D, Brazinova A, Rusnak M, et al. Epidemiology of traumatic brain injuries in Europe: a cross-sectional analysis. Lancet Public Health 2016, doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(16)30017-2.

- Majdan M, Mauritz W, Brazinova A, Rusnak M, et al. Severity and outcome of traumatic brain injuries (TBI) with different causes of injury. Brain Inj., 2011, doi: 10.3109/02699052.2011.581642.

- Capizzi A, Woo J, and Verduzco-Gutierrez M. Traumatic Brain Injury. Med. Clin. North Am. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2019.11.001.

- Lecky FE, Otesile O, Marincowitz C, Majdan M, et al. The burden of traumatic brain injury from low-energy falls among patients from 18 countries in the CENTER-TBI Registry: A comparative cohort study. PLoS Med.2021, doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003761.

- Huijben JA, Wiegers EJA, Lingsma HF, Citerio G et al. Changing care pathways and between-center practice variations in intensive care for traumatic brain injury across Europe: a CENTER-TBI analysis. Intensive Care Med.2020, doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05965-z.

- Steyerberg EW, Wiegers E, Sewalt C, Buki A, et al. Case-mix, care pathways, and outcomes in patients with traumatic brain injury in CENTER-TBI: a European prospective, multicentre, longitudinal, cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2019, doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30232-7.