Developed by: Iulia Vadan, Silvina Ilut

- Epidemiology of TBI

- Elderly Population and TBI

- What is TBI?

- What is the economic burden of TBI?

- TBI monitoring and treatment in ICU

- What is the role of rehabilitation in TBI?

- The transition from hospital to home

- What is CENTER-TBI?

- The purpose of CENTER-TBI

- Timing of the transition

- CENTER-TBI results

- CENTER-TBI conclusions

- References

This article touches the aspects related to what happens to a patient suffering a TBI and the lessons from the CENTER-TBI study on the outcome of TBI patients.

Keywords: traumatic brain injury (TBI), management, rehabilitation, care transition

Epidemiology of TBI

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) represents a significant medical, socioeconomic, and healthcare problem worldwide. It is one of the most important causes of disability and mortality, especially in young individuals [1, 2], being considered the “silent epidemic” as society is mostly unaware of the magnitude of the problem [3].

It is well-known that disability in TBI patients adversely impacts:

- employment

- life quality

- functional independence

- social and emotional well-being

- life expectancy [4] .

As proven by several epidemiological studies, high-energy road traffic accidents are the main reason the incidence of TBI is rising globally [1, 2]. Other common causes include low- and high-level falls, injuries at the workplace, and violence or assault [5].

Elderly Population and TBI

With the increase of the older population around the world, the impact of TBI on these patients has become a significant healthcare issue. The elderly population is at an increased risk of TBI with higher mortality rates and, in comparison with the young population, a worse functional outcome. In 2030 it is expected that the incidence of chronic subdural hematoma will double. In the post-acute phase for these patients, care is complex and requires a multidisciplinary team of nurses, rehabilitation specialists, case managers, and personal caregivers such as family or friends [6].

What is TBI?

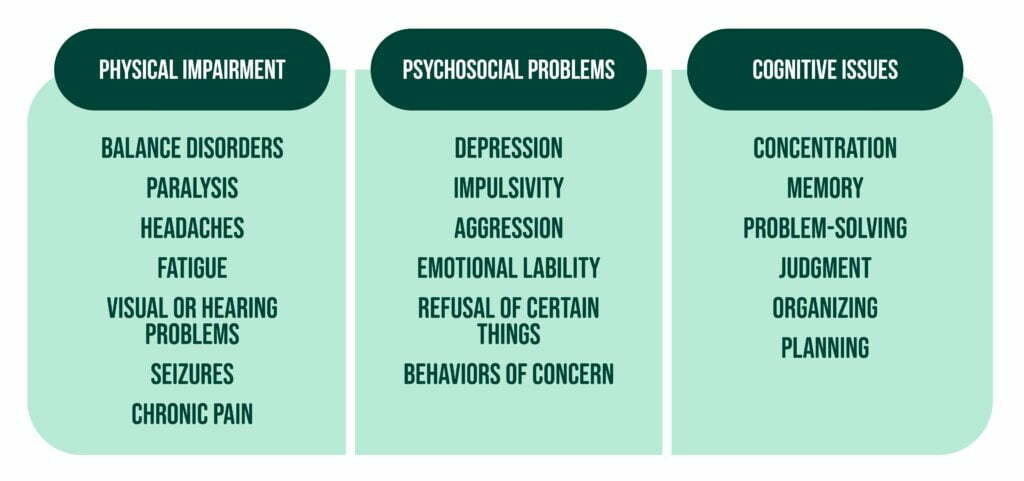

A TBI may represent a significant physical, psychosocial, and cognitive impairment, leading to a lifetime of continuous need for health care and support, as illustrated in the graphic below:

It is essential to understand that sometimes the cognitive deficits resulting after a brain injury are even more critical and significant for the patient and the caregiver than the physical ones [7].

What is the economic burden of TBI?

The economic burden of health care provision for people with head injuries worldwide is substantial and represents a concern for funders of health care services. For example, the USA is said to spend approximately 9 to 10 billion dollars per year on acute care and rehabilitation for people who suffered a TBI. That is why there is a need to ensure wise spending and investment of money in the treatment and rehabilitation of TBI patients. Recent reviews studying the global impact of TBI concluded that approximately 10 million people experience a TBI each year, leading to either death or hospitalization. In addition, 450-700/100,000 people annually who suffer a TBI need hospitalization or a referral to a medical practitioner depending on the country [8].

The direct and indirect annual medication cost associated with TBI is estimated to be somewhere between 60 and 76 billion dollars, with the majority of costs being associated with moderate and severe injuries. Moreover, patients with greater severity of the TBI have been associated with the need for institutionalization in long-term nursing facilities [4].

Hospital admission is usually necessary for moderate and severe TBI, and it is well known that TBI offers the most challenging areas in modern rehabilitation [9]. See in our previous article the impact of COVID-19 in TBI.

TBI monitoring and treatment in ICU

Some of the patients suffering from brain injury need monitoring and treatment in the ICU. Because ICU beds are a costly and limited resource, admission is justified for those patients with severe injuries needing acute life-sustaining physiological support. On the other hand, ICU admission could also be justified even for a proportion of patients with milder TBIs as their state could easily deteriorate due to their comorbidities or because their needs of care are still too important to be adequately provided at the ward. However, there are not generally accepted and applied admission criteria for less severe brain-injury patients. Therefore, the decision is mainly based on the clinician’s experience, the institutional determinants, and service configuration [10].

What is the role of rehabilitation in TBI?

World Health Organization defines rehabilitation as “a set of interventions designed to optimize functioning and reduce disability in individuals with a health condition who experience some form of limitation in functioning across the continuum of care and throughout the lifespan” [11].

Rehabilitation after a brain injury, especially in the case of a severe TBI, can be a long process. Because of this, the coordination of care is essential for optimal neurologic recovery. The survival rate in the acute phase of TBI increases due to the progress in the medical interventions from the last years. Thus, the number of patients needing long-term management of disabilities resulting from injury has risen [6].

More studies are needed to evaluate these patients’ pathways from presenting to the Emergency Department until being released from the hospital. However, it is well established that the transitions of patients with complex health problems after a TBI need careful planning and support.

A rehabilitation specialist should be consulted as early as possible in the acute hospitalization, especially in the case of a severe TBI, and included in the daily rounds and care. First, the clinicians evaluate these patients’ swallowing, mobility, spasticity, and neurobehavioral disorders starting from the ICU or hospital ward. Then, they decide if there is a need for more interdisciplinary consults, particularly for physical medicine and rehabilitation.

The transition from hospital to home

Frequently, at hospital discharge, the patients have a different medication plan than their prehospital regimens. Similar to patients with other diagnoses such as diabetes and hypertension, patients with TBI and their caregiver or family need education specific for this type of pathology. The medication list of patients should be reviewed and updated accordingly [6].

A relatively new area of research is represented by the transition from the hospital to home or nursing facility. It is a critical phase where patients and their families develop a greater understanding of the impact of the injury on their daily life. It represents an important moment when the responsibility of care shifts from the health care services to family members or friends. This transition constitutes a moment when patients and caregivers feel vulnerable and unsupported by health care services. It frequently involves an important change in social roles and responsibility for the patient and the carer. It is necessary to understand the patient, the family, and the social context from the health workers to facilitate the transition. They also need to be clear about the rehabilitation needs of the patient and his ongoing health. The patient and his caregiver’s implication as equal partners in the decision-making is required to facilitate a smooth transition [12].

What is CENTER-TBI?

The Collaborative European NeuroTrauma Effectiveness Research in Traumatic Brain Injury (CENTER-TBI) study was a multi-center, observational, longitudinal, cohort study that followed the admission and treatment of patients with TBI from Israel and Europe over 3 years, from December 2014 to December 2017. The inclusion criteria were clinical diagnosis of TBI, indication for CT imaging, presentation within 24 hours of injury, and informed consent. The exclusion criterion was a pre-existing severe neurological disorder that may influence the outcome assessment. The enrolled patients were stratified into 3 groups according to the initial clinical care pathway:

- ER stratum consisted of patients evaluated in the emergency room and then discharged

- Admission stratum, formed from patients admitted to a hospital ward

- ICU stratum consisted of patients admitted directly to an ICU, from the Emergency Department or another hospital.

The purpose of CENTER-TBI

This article aimed to follow the transition of care for these patients from hospital admission to discharge home and post-acute care during the first 6 months after the head injury. Patients who died during admission were excluded. Care transitions were defined as moments during a care pathway when the patient was transferred from one treatment facility to another or discharged from organized TBI care. Seven categories were used to describe patient transitions:

- from hospital ER to an intensive or high care unit

- neurosurgical ward

- neurological ward

- other wards

- rehabilitation unit

- nursing home

- home

- another hospital

Transitions to and from CT imaging, MRI, or surgery were excluded, and their last registered transition was designated as their post-acute discharge destination.

This study classified injury causes:

- road traffic accidents

- falls

- violence

- suicide

- others.

Glasgow Coma Scale score was used to evaluate the severity of the head injury. The Injury Severity Score (ISS) depicted overall trauma severity. The Glasgow Outcome Scale-Extended (GOSE) score was used to assess 6-month outcomes as favorable (if the score was between 5 and 8) or non-favorable (if the score was between 1 and 4), but the patients with a GOSE score of 1, signifying death, were excluded.

Timing of the transition

Treatment centers described the timing of each transition as appropriate, premature, or delayed, based on the patient’s clinical assessment from the physician and his opinion if the patient is ready or not to be transferred. The Eurovac classification scheme classified the geographical region. Living arrangements were also assessed by the data collected from the number of co-habitants, and for the patients living alone, there was a yes or no designation. The functional impact of the patient’s medical comorbidity before the TBI was also considered.

CENTER-TBI results

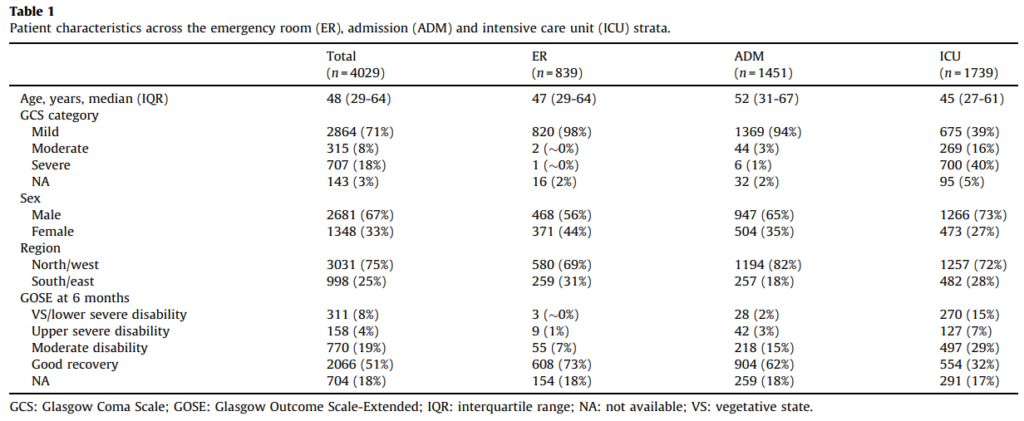

Source: Care transitions in the first 6 months following traumatic brain injury:

Lessons from the CENTER-TBI study

The results showed that at 6 months, 4029 patients were alive and eligible for study inclusion. The median number of transitions for these patients was 3, except for patients older than 70 years who had a median of 2. Overall, the median age was 48 years. Most patients were male, had a mild TBI, and showed favorable outcomes at 6 months. In addition, patients with mild head injury showed mainly were in the ER stratum and the admission stratum, with ICU stratum containing mostly severe cases of TBI.

Only approximately 10% of patients reported having at least one premature or delayed transition. In the premature subgroup, the prime transitions were to home or to other hospitals. The delayed subgroup mixed the main transitions from CUs, other hospitals, neurosurgical wards, and rehabilitation facilities. The highest transition variation was observed in the ICU stratum because these patients had more severe injuries and needed more days in the hospital.

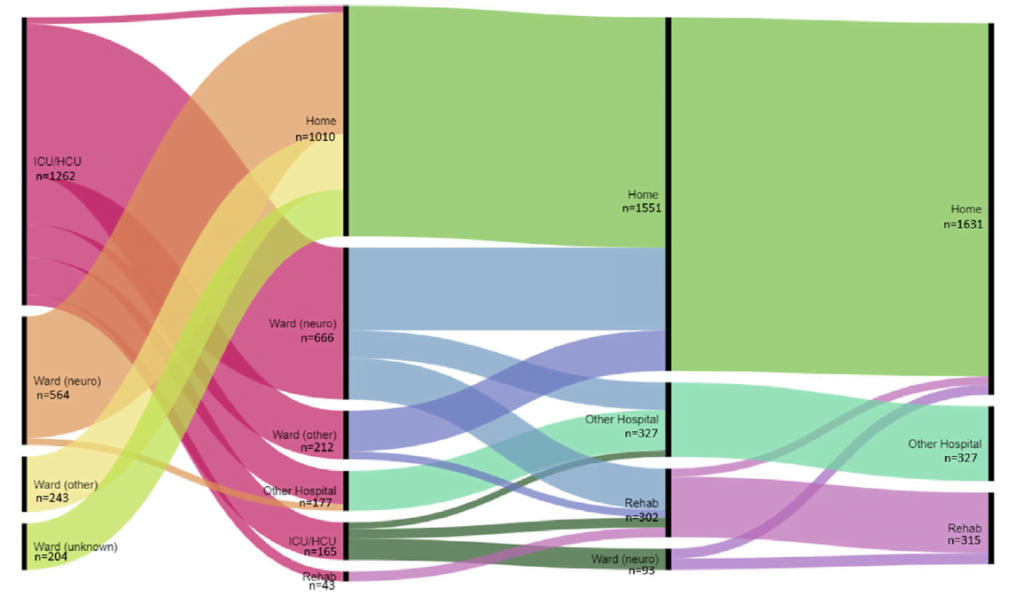

The 378 care pathways that the CENTER-TBI study revealed are a statement of the complexity TBI is presenting.

Source: Care transitions in the first 6 months following traumatic brain injury:

Lessons from the CENTER-TBI study

CENTER-TBI conclusions

Patients with milder TBI recover faster, while those with severe TBI, major trauma, or increased age have a poorer functional outcome. In addition, a high number of transitions was linked to an unfavorable outcome at 6 months.

Previous studies reported 3 factors that influenced transitions for patients suffering a head injury:

- personal/individual characteristics

- family/caregiving factors

- professional/service factors.

Patients from South/East Europe showed poorer outcomes, but we must keep in mind that there is high variability in the number of curative and rehabilitation beds across Europe.

To ensure that the transition experience from hospital to home or nursing facility is optimal for the patients with a head injury and the caregiver, recommendations for policy and practices should focus on improving services. For example, counseling should be available for patients and their families or caregiver at multiple moments during the transition process, and it should represent a priority for health care professionals. Moreover, there should be an increase in interaction between the patient or family and the staff to allow them to feel comfortable asking questions and enhancing their knowledge and understanding about the transition process. Finally, all the strategies should aim to make the transition be perceived as positive and successful for everyone involved in the transition from hospital to home or nursing facility (health care professional, patient, family, caregiver) [7].

The CENTER-TBI study revealed the highly diverse and complex TBI care pathways. The variation and a high number of pathway possibilities suggest the need for regulations to improve the outcomes for all patients.

References

1. Maas, A I, Stocchetti, N & Bullock, R. Moderate and severe traumatic brain injury in adults. Lancet Neurol. 7, 728–741 (2008). DOI: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70164-9

2. Huijben, J. A. et al. Changing care pathways and between-center practice variations in intensive care for traumatic brain injury across Europe: a CENTER-TBI analysis. Intensive Care Med. 46, 995–1004 (2020). DOI: 10.1007/s00134-020-05965-z

3. Roozenbeek, B., Maas, A. I. R. & Menon, D. K. Changing patterns in the epidemiology of traumatic brain injury. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 9, 231–236 (2013). DOI: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.22

4. Eum, R. S. et al. Predicting Institutionalization after Traumatic Brain Injury Inpatient Rehabilitation. J. Neurotrauma 32, 280–286 (2015). DOI: 10.1089/neu.2014.3351

5. Majdan, M. et al. Severity and outcome of traumatic brain injuries (TBI) with different causes of injury. Brain Inj. 25, 797–805 (2011). DOI: 10.3109/02699052.2011.581642

6. Puccio, A. M., Anderson, M. W. & Fetzick, A. The Transition Trajectory for the Patient with a Traumatic Brain Injury. Nurs. Clin. North Am. 54, 409–423 (2019). DOI: 10.1016/j.cnur.2019.04.009

7. Piccenna, L., Lannin, N. A., Gruen, R., Pattuwage, L. & Bragge, P. The experience of discharge for patients with an acquired brain injury from the inpatient to the community setting: A qualitative review. Brain Inj. 30, 241–251 (2016). DOI: 10.3109/02699052.2015.1113569

8. Levack, W. M. M., Kayes, N. M. & Fadyl, J. K. Experience of recovery and outcome following traumatic brain injury: a metasynthesis of qualitative research. Disabil. Rehabil. 32, 986–999 (2010). DOI: 10.3109/09638281003775394

9. Borg, J. et al. Trends and Challenges in the Early Rehabilitation of Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury: A Scandinavian Perspective. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 90, 65–73 (2011). DOI: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181fc80e7

10. Volovici, V. et al. Intensive care admission criteria for traumatic brain injury patients across Europe. J. Crit. Care 49, 158–161 (2019). DOI: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.11.002

11. Jacob, L. et al. Predictors of Access to Rehabilitation in the Year Following Traumatic Brain Injury: A European Prospective and Multicenter Study. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 34, 814–830 (2020).DOI: 10.1177/1545968320946038

12. Abrahamson, V., Jensen, J., Springett, K. & Sakel, M. Experiences of patients with traumatic brain injury and their carers during transition from in-patient rehabilitation to the community: a qualitative study. Disabil. Rehabil. 39, 1683–1694 (2017). DOI: 10.1080/09638288.2016.1211755