Authors:

- Luis Rafael Moscote-Salazar. MD; Colombian Research Group in Neurocritical Care, Colombia.

- Iván David Lozada-Martínez. MS; Colombian Research Group in Neurocritical Care, Colombia

- Maria Paz Bolaño-Romero, MS; Colombian Research Group in Neurocritical Care, Colombia

Keywords: neurotrauma, humanization, critical care, neuroethics, patient care

Introduction | Humanization in Neurotrauma and Neurocritical Care

The advancements in medicine and unstoppable technological progress have led to a depersonalization of medical practice [1]. As the medical vocation is a condition inherent to the medical act, the concept of the human being as unique needs to be one of the pillars of the individualized approaches [1,2]. Humanization, as a notion, is complex and aims to visualize the patient as a whole, considering the pathophysiological component of a disease, as well as the environment and common human experiences, such as fear, frustration, and joy.

With the emergence of patients and family-centered care (PFC) in the United States, a new approach was developed, one centered around respect for the decisions of the patient and their families. This perspective represents a key factor for the improvement of care practices and a stepping stone for the further development of comprehensive approaches [3].

Respect for the autonomy and decisions of the patients is crucial for a harmonious doctor-patient-family relationship [2]. Humanization of intensive care should focus on the patients, guaranteeing their dignity and respect for their values in the context of the best evidence and involving the family in all decisions and, thus, in the global care process [4]. Critical patients face a different environment than their daily life, and the description of Post Intensive Care Syndrome forces us to understand that a significant percentage of patients describe their stay in the ICU as not pleasant [3].

In neurocritical care, humanization means restoring the doctor’s sense of humanity. As such, the therapeutic strategy must focus on guaranteeing the well-being of the patients, regardless of their prognosis, framed in an honest and ethical practice [4]. Neurointensive specialists should incorporate the essential aspects of humanized medical practice in their daily activities. Patient- and family-centered care needs to become a path that allows for the strengthening of medical practice in neurocritical care [5,6].

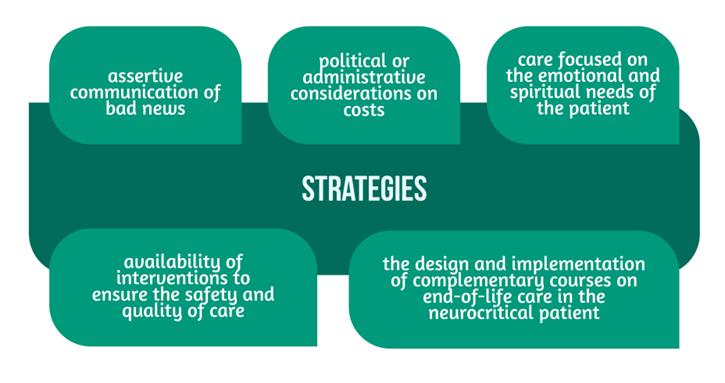

Some strategies to reinforce humanization in neurocritical care are further described.

Continuing education by the health professionals

Continuing education is the process by which physicians acquire knowledge based on emerging evidence, debate topics of practice interest and decision-making, and broaden their vision of their practice.

Some essential strategies include those showcased in Figure 1 [7,8].

Other factors that may influence the patient’s overall outcomes are addressed as well [9].

Changing the approach – accommodations for the patients and their families

During the acute phase of the disease, uncertainty about the patient’s prognosis affects the patient and his or her family, which, together with other factors (e.g., educational, economic, social, and cultural), could have a negative impact on the patient’s physical and emotional health [10,11].

Although the care load in intensive care units is high, it is necessary to modify the equipment to better accommodate the family and the patient, to address the needs and generate peace of mind during the hospital stay, but also to facilitate the rehabilitation process and patient reintegration into society.

Promoting teamwork and multidisciplinary techniques

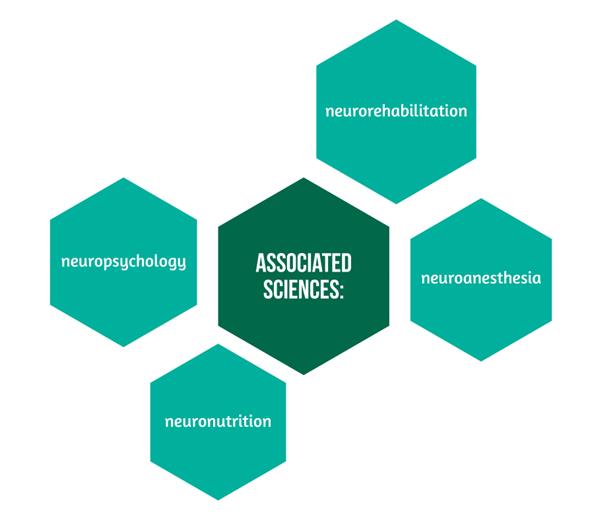

To obtain the best results in critical care, it is necessary to see the patient as a whole [10,11]. Thus, all neurocritical care units should have specialized groups in charge of maintaining neurological integrity. The approach to neurotrauma care should also involve associated sciences, including those showcased in Figure 2.

Specialists working in these fields and other disciplines should be available to listen to the patient’s condition and act in a timely manner [12,13]. Although there are tools (e.g., imaging) that allow observing the integrity of brain structures, the behavior and mood of the patient do not always correlate with this evidence.

Verifying patient care, caregiver education, and financial needs

Especially in low- and middle-income countries, where most of the patients come from rural areas or are vulnerable people, it would be necessary to strengthen the health education of the caregiver and the patient and to consider the economic impact of the disease on the household.

Patient follow-up units should be created to provide supplies and monitor patient recovery. This would reduce readmissions and complications in local areas where interventional procedures are performed, and ensure that the patient complies with the recovery period, without affecting the financial situation in the household.

Unfortunately, many regions of the world with high indicators of neurological disease burden lack specialized neurocritical care centers. Supporting services such as neurorehabilitation, neuro-nutrition, and neuroeducation would significantly improve the medium- and long-term prognosis of patients with neurocritical illnesses [13].

To solve this, it becomes imperative to implement prospective studies that demonstrate the real impact of neurocritical pathology on the quality of life of the affected and their relatives and to expose the dynamics that occur between low-, middle- and high-income countries, in order to design programs adapted to the needs of each context, especially in the presence of a recently described condition for which there is no known long-term prognosis: post-COVID 19 neurological syndrome [14], which could modify the prognosis of those affected with a history of neurovascular or neurodegenerative disorders [14].

Prioritizing and strictly monitoring palliative care

One of the most discussed issues is the management of palliative care in the critically ill patient. Neuroethics is an emerging branch of neuroscience that promises to answer questions that hinder the interaction between the decisions made by the medical team and the perception of care by patients and their families.

Neuroethics is a field to be currently considered in palliative neurocritical management, to provide adequate care at the end of life, and ensure that the rights and wishes of the patient are respected, persevering their peace of mind and that of their families, as well as mitigating the impact of situations that generate fear and agony against difficulties such as pain, disability, impaired quality of life, and death. It is compulsory to educate the medical team on the study of this discipline and its benefits in healthcare practice.

There are still many challenges when considering humanization in medical practice. This varies depending on events that disrupt the harmonious relationships among the different actors involved in the process.

Short- and medium-term objectives should be set to achieve progress in solving these problems and promoting medical care and the integrity of healthcare workers, patients, and their families.

For more insight into neurotrauma, from the same author, visit:

- Osmotherapy in Severe TBI

- Hypothermia as a neuroprotective strategy after TBI

- Prevention of Neurotrauma is the Best Treatment

- Neurotrauma and info-pollution: A call for action

References

- La Calle GH, Martin MC, Nin N. Seeking to humanize intensive care. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2017;29(1):9-13. doi: 10.5935/0103-507X.20170003

- Gerteis M, Edgman-Levitan S, Daley J, Delbanco TL, eds. Through the Patient’s Eyes: Understanding and Promoting Patient-Centered Care. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1993:20. Available at: https://psnet.ahrq.gov/issue/through-patients-eyes-understanding-and-promoting-patient-centered-care

- Locke M, Eccleston S, Ryan CN, Byrnes TJ, Mount C, McCarthy MS. Developing a Diary Program to Minimize Patient and Family Post-Intensive Care Syndrome. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2016; 27(2):212-20. DOI: 10.4037/aacnacc2016467

- La Calle GH. My favorite slide: The ICU and the human care bundle. NEJM Catalyst, 2018. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.18.0215

- Velasco Bueno JM, La Calle GH. Humanizing Intensive Care: From Theory to Practice. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2020; 32(2):135-147. DOI: 10.1016/j.cnc.2020.02.001

- Busl KM, Bleck TP, Varelas PN. Neurocritical Care Outcomes, Research, and Technology: A Review. JAMA Neurol. 2019; 76(5):612-618. DOI: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4407

- Robinson MT, Holloway RG. Palliative Care in Neurology. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017; 92(10):1592-1601. DOI: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.08.003

- Crooms RC, Gelfman LP. Palliative Care and End-of-Life Considerations for the Frail Patient. Anesth Analg. 2020; 130(6):1504-1515. DOI: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004763

- Aruga T. Clinical Ethics in Neurological Emergencies and Critical Care. Brain Nerve. 2020; 72(7):767-775. doi: 10.11477/mf.1416201594.

- Galvin IM, Leitch J, Gill R, Poser K, McKeown S. Humanization of critical care-psychological effects on healthcare professionals and relatives: a systematic review. Can J Anaesth. 2018; 65(12):1348-1371. DOI: 10.1007/s12630-018-1227-7

- Bambi S, Iozzo P, Rasero L, Lucchini A. COVID-19 in Critical Care Units: Rethinking the Humanization of Nursing Care. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2020; 39(5):239-241. DOI: 10.1097/DCC.0000000000000438

- Casaletto KB, Heaton RK. Neuropsychological Assessment: Past and Future. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2017; 23(9-10):778-790. DOI: 10.1017/S1355617717001060

- Ortega-Sierra MG, Durán-Daza RM, Carrera-Patiño SA, Rojas-Nuñez AX, Charry-Caicedo JI, Lozada-Martínez ID. Neuroeducation and neurorehabilitation in the neurosurgical patient: programs to be developed in Latin America and the Caribbean. J Neurosurg Sci. 2021. DOI: 10.23736/S0390-5616.21.05439-4

- Camargo-Martínez W, Lozada-Martínez I, Escobar-Collazos A, Navarro-Coronado A, Moscote-Salazar L, Pacheco-Hernández A, Janjua T, Bosque-Varela P. Post-COVID 19 neurological syndrome: Implications for sequelae’s treatment. J Clin Neurosci. 2021; 88:219-225. DOI: 10.1016/j.jocn.2021.04.001